When you buy an ETF, you're not just buying a single fund-you're stepping into a complex system that changes how every stock inside it behaves. It sounds simple: you pick an ETF that tracks the S&P 500, click buy, and you own a slice of 500 companies. But behind that click, something deeper is happening. The rise of ETFs hasn’t just made investing easier-it’s rewired the way liquidity flows through the entire stock market. And that shift is making individual stocks harder to trade, especially for certain kinds of investors.

ETFs Pull Liquidity Away from Individual Stocks

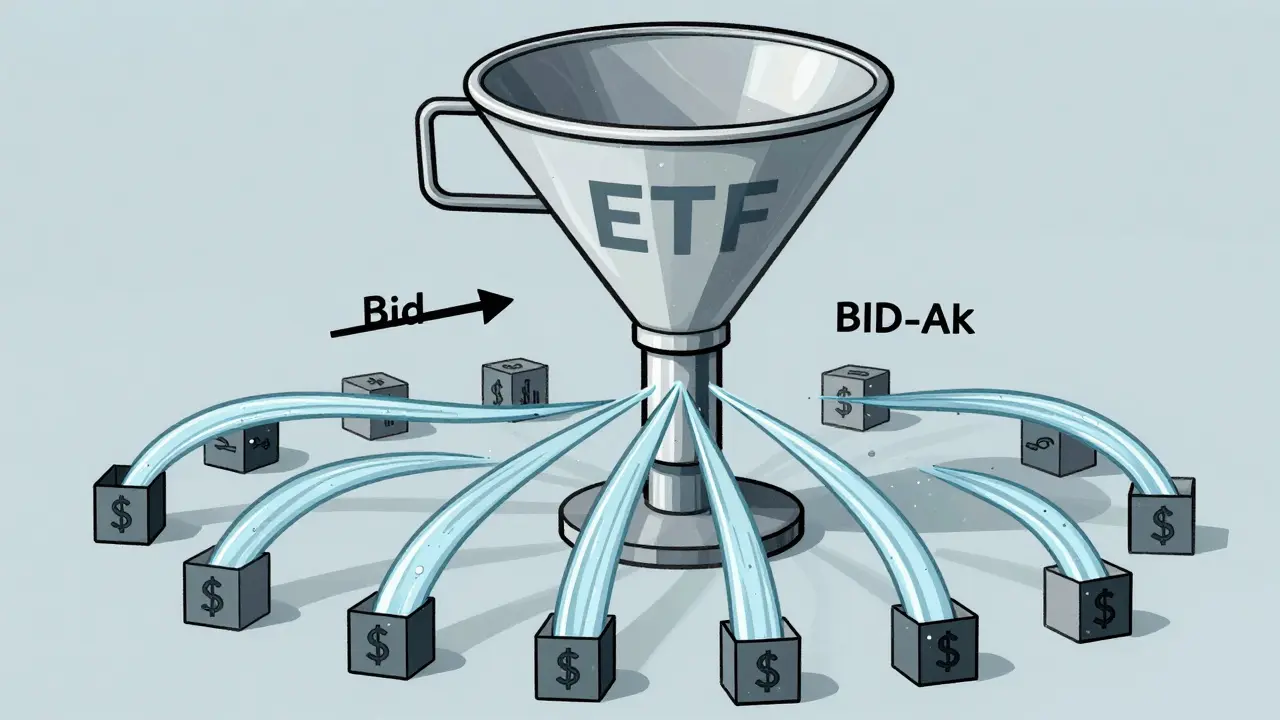

Think of liquidity like water in a river. The more people swim in one spot, the easier it is for others to jump in and out without causing ripples. That’s what happens with popular ETFs like SPY or IVV. Trillions of dollars flow through them every day. But here’s the twist: that liquidity didn’t appear out of nowhere. It was pulled from the individual stocks those ETFs hold. A 2010 study by Sophia Jihae Wee Hamm found that as ETFs grew in popularity, uninformed investors-people who don’t have inside information or advanced trading strategies-started avoiding individual stocks. Why? Because trading individual stocks meant running the risk of being on the wrong side of a trade with someone who knew more. ETFs became a safe harbor. You don’t need to know whether Apple will beat earnings or if Tesla’s supply chain is crumbling. You just buy the ETF. And that migration left individual stocks with fewer buyers and sellers. The result? Stocks held in highly diversified ETFs became less liquid. Hamm’s research showed that when an ETF holds 200+ stocks, the liquidity drain on each individual stock is stronger than if the ETF only held 10. Why? Because when millions of people trade the ETF, the underlying stocks aren’t being traded at all. They’re just sitting there, quietly accumulating imbalance. That imbalance shows up as wider bid-ask spreads, slower trade execution, and more price swings when big orders hit.Two Layers of Liquidity-Most People Miss One

Here’s where most retail investors get it wrong. They think liquidity = trading volume. If an ETF trades 10 million shares a day, they assume it’s super liquid. But that’s only half the story. ETFs have two layers of liquidity: the secondary market (where you and I trade) and the primary market (where Authorized Participants, or APs, work behind the scenes). When you buy an ETF share on the open market, you’re trading with another investor. But if demand spikes, APs step in. They create new ETF shares by buying the actual basket of stocks-say, 50,000 shares of Microsoft, 30,000 of Amazon, etc.-and delivering them to the ETF issuer in exchange for new ETF shares. The reverse happens when people sell: APs redeem ETF shares for the underlying stocks. This means even if an ETF only trades 100,000 shares a day, it can still be highly liquid because APs can create or destroy shares on demand. That’s why a small ETF tracking a niche index can still be easy to trade. Its liquidity isn’t tied to how many people are buying it-it’s tied to how easy it is to assemble the underlying basket. State Street Global Advisors and Schwab both confirm: an ETF’s liquidity is always at least as strong as its underlying holdings. If the stocks inside are liquid (like those in the S&P 500), the ETF inherits that strength. If the underlying stocks are illiquid (say, small-cap biotech firms), the ETF’s liquidity depends entirely on APs’ ability to source those shares.Why ETFs Don’t Work Like Mutual Funds

Mutual funds and ETFs both bundle stocks. But their liquidity mechanics couldn’t be more different. Mutual funds trade once a day at the closing price. If you want to sell, you wait until the market closes. No intraday trading. No real-time price changes. No secondary market. That means mutual funds don’t create liquidity pressure on individual stocks-they just sit there, collecting assets. ETFs? They trade like stocks. Every second, prices move. Every minute, volume piles up. And that constant trading creates a feedback loop: more volume → more liquidity → more investors → even more volume. Khomyn’s 2024 study found that ETFs with higher trading volumes have 7.31 times more activity than their less-traded cousins-even if they track the same index. That’s not coincidence. It’s a self-reinforcing cycle. And here’s the kicker: unlike mutual funds, where high turnover hurts performance by increasing costs, ETFs actually get better as they get more popular. The market rewards them with tighter spreads, faster execution, and lower slippage. That’s why short-term traders, hedge funds, and algorithmic systems flock to the most liquid ETFs-even if they pay slightly higher fees.

The Hidden Cost: Liquidity Externalities

There’s a dark side to this efficiency. When everyone rushes to the most liquid ETF, it creates a kind of economic trap. Khomyn’s research calls it a “liquidity externality.” Imagine two ETFs tracking the same index: one charges 0.03% in fees, the other 0.08%. The cheaper one is objectively better. But if the expensive one trades 10 times more volume, most investors will pick it anyway. Why? Because they want to trade fast, with tight spreads and no slippage. They’re willing to pay extra for convenience. This creates a prisoner’s dilemma. As a group, we’d all be better off if we all switched to the cheap ETF. But as individuals, we’re incentivized to stick with the liquid one. The result? The high-fee ETF grows, the low-fee one withers, and investors collectively pay more. It’s not just about fees. It’s about who gets hurt. The stocks inside the ETFs that aren’t getting traded anymore? They become harder to buy or sell. Market makers raise their spreads. Institutional traders take longer to execute. And if a big fund needs to dump 10 million shares of a small-cap stock, it might not find enough buyers-because those buyers are all in the ETF.What This Means for You as a Trader

If you’re a retail investor buying ETFs for long-term growth, this probably doesn’t affect you much. You’re not trying to trade 10,000 shares in 10 minutes. You’re holding for years. But if you’re trading actively, even occasionally, you need to understand what’s going on. Don’t assume trading volume equals liquidity. A small ETF with low volume might still be easy to trade if its underlying stocks are liquid and APs are active. Watch the underlying index. An ETF tracking the Nasdaq-100 will behave very differently from one tracking obscure emerging market bonds. The former has deep, liquid stocks. The latter might be a ticking time bomb. Be wary of crowded ETFs. If 80% of investors in a sector are in one ETF, you’re not just investing in the index-you’re betting on the liquidity of that ETF. If something breaks (say, APs stop creating shares), the ETF could trade at a big premium or discount. For large orders, use limit orders. If you’re trading more than a few hundred shares of an ETF, don’t use market orders. Prices can move fast if the primary market is slow to respond.

Sabrina de Freitas Rosa

February 9, 2026 AT 10:07Erika French Jade Ross

February 10, 2026 AT 14:18Geoffrey Trent

February 11, 2026 AT 03:49John Weninger

February 12, 2026 AT 01:38Omar Lopez

February 13, 2026 AT 06:45